What Is A File With No Background Called

| Symphony No. 13 | |

|---|---|

| Babi Yar | |

| by Dmitri Shostakovich | |

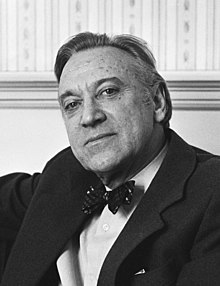

Dmitri Shostakovich in 1950 | |

| Key | B flat minor |

| Catalogue | Op. 113 |

| Text | Five poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko |

| Language | Russian |

| Composed | 1962 |

| Duration | one hour |

| Movements | 5 |

| Scoring | Bass soloist, men's chorus, and large orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Appointment | December xviii, 1962 (1962-12-eighteen) |

| Location | Moscow |

| Usher | Kirill Kondrashin |

| Performers |

|

Dmitri Shostakovich'south Symphony No. 13 in B-flat minor, Op. 113 (subtitled Babi Yar ) is an hour-long work for bass soloist, men'due south chorus, and large orchestra that is laid out in five movements, each a setting of a Yevgeny Yevtushenko verse form. This unusual course gives rise to various descriptions: choral symphony, song cycle, giant cantata. The five earthily vernacular[one] poems portray Soviet life one attribute at a time.

The symphony was completed on July 20, 1962, and first performed in Moscow in December of that year. Kirill Kondrashin conducted the premiere later on Yevgeny Mravinsky declined the assignment. Vitaly Gromadsky sang the solo part aslope the combined choruses of the RSFSR Land University and Gnessin Institute and the Moscow Philharmonic.

Movements [edit]

The symphony consists of five movements.

- Babi Yar: Adagio (15–18 minutes)

-

- In this motility, Shostakovich and Yevtushenko transform the 1941 massacre past Nazis of Jews at Babi Yar, near Kyiv, into a denunciation of anti-Semitism in all its forms. (Although the Soviet authorities did not erect a monument at Babi Yar, it notwithstanding became a place of pilgrimage for Soviet Jews.)[two] Shostakovich sets the poem as a series of theatrical episodes — the Dreyfus thing, the Białystok pogrom and the story of Anne Frank —, extended interludes in the main theme of the verse form, lending the move the dramatic structure and theatrical imagery of opera while resorting to graphic illustration and bright word painting. For example, the mocking of the imprisoned Dreyfus by poking umbrellas at him through the prison confined may be in an accentuated pair of 8th notes in the contumely, with the build-upward of menace in the Anne Frank episode, culminating in the musical paradigm of the breaking downwardly of the door to the Franks' hiding place, which underlines the hunting down of that family.[3] The Russian people are not the anti-Semites, they are "internationals", and the music is briefly hymn-like before dissolving into the cacophony of those who falsely merits to be working for the people.[ citation needed ]

- Humor: Allegretto (8–9 minutes)

-

- Shostakovich quotes from the third of his Half-dozen Romances on Verses by British Poets, Op. 62 (Robert Burns' "Macpherson Earlier His Execution") to colour Yevtushenko's imagery of the spirit of mockery, endlessly murdered and incessantly resurrected,[one] denouncing the vain attempts of tyrants to shackle wit.[2] The move is a Mahlerian gesture of mocking burlesque,[3] not simply light or humorous only witty, satirical and parodistic.[4] The irrepressible energy of the music illustrates that, simply as with courage and folly, humor, fifty-fifty in the form of "laughing in the face of the gallows" is both irrepressible and eternal (a concept, incidentally, also present in the Burns poem).[5] He besides quotes a melody of the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion by Bartók ironically, as response for the criticism toward his Symphony no. 7.

- In the Store: Adagio (10–13 minutes)

-

- This movement is about the hardship of Soviet women queueing in a store. Information technology is also a tribute to patient endurance. This arouses Shostakovich's pity no less than racial prejudice and gratuitous violence.[3] Written in the form of a complaining, the chorus departs from its unison line in the music's two last harmonized chords for the only time in the entire symphony, catastrophe on a plagal cadence functioning much the same every bit a liturgical amen.[3]

- Fears: Largo (11–13 minutes)

-

- This motility touches on the subject field of suppression in the Soviet Union and is the about elaborate musically of the symphony's five movements, using a diverseness of musical ideas to stress its message, from an aroused march to alternate soft and violent episodes.[vi] Notable hither are the orchestral effects — the tuba, for instance, hearkening dorsum to the "midnight arrest" section of the first movement of the Quaternary Symphony — containing some of the composer's most adventurous instrumental touches since his Modernist period.[1] It also foresees some of Shostakovich'due south after practices, such as an xi-notation tone row played by the tuba as an opening motif.

-

- Harmonic ambiguity instills a deep sense of unease equally the chorus intones the first lines of the poem: "Fears are dying-out in Russia." ("Умирают в России страхи.")[7] Shostakovich breaks this mood just in response to Yevtushenko's agitprop lines, "We weren't afraid/of construction work in blizzards/or of going into battle nether shell-burn," ("Не боялись мы строить в метели, / уходить под снарядами в бой,)[7] parodying the Soviet marching song Smelo tovarishchi v nogu ("Bravely, comrades, march to step").[3]

- Career: Allegretto (xi–thirteen minutes)

-

- While this motion opens with a pastoral duet by flutes over a B ♭ pedal bass, giving the musical upshot of sunshine later a tempest,[five] it is an ironic set on on bureaucrats, touching on cynical cocky-interest and robotic unanimity while as well a tribute to genuine creativity.[2] It follows in the vein of other satirical finales, especially the Eighth Symphony and the Fourth and Sixth Cord Quartets.[1] The soloist comes onto equal terms with the chorus, with sarcastic commentary provided by the bassoon and other wind instruments, as well as rude squeaking from the trumpets.[5] Information technology also relies more than than the other movements on purely orchestral passages equally links between vocal statements.[6]

Instrumentation [edit]

The symphony calls for a bass soloist, bass chorus, and an orchestra with the following instrumentation.

Overview [edit]

Background [edit]

Shostakovich's interest in Jewish subjects dates from 1943, when he orchestrated the opera Rothschild's Violin past Jewish composer Venyamin Fleishman. This piece of work independent characteristics which would go typical of Shostakovich'south Jewish idiom — the Phrygian style with an augmented third and the Dorian mode with an augmented fourth; the iambic prime (a serial of 2 notes on the same pitch in an iambic rhythm, with the first notation of each phrase on an upbeat); and the standard accompaniments to Jewish klezmer music. Afterwards completing the opera, Shostakovich used this Jewish idiom in many works, such equally his Second Piano Trio, the Outset Violin Concerto, the Fourth String Quartet, the song bicycle From Jewish Folk Poesy, the 24 Preludes and Fugues and the Four Monologues on Texts past Pushkin. The composition of these works coincided roughly with the virulent state-sanctioned anti-Semitism prevalent in Russia in those years, as part of the anti-Western campaign of Zhdanovshchina. Shostakovich was drawn to the intonations of Jewish folk music,[8] explaining, "The distinguishing feature of Jewish music is the ability to build a jolly melody on sad intonations. Why does a man strike upwardly a jolly song? Because he is sad at heart."[9]

In the 13th Symphony, Shostakovich dispensed with the Jewish idiom, as the text was perfectly clear without it.[2]

Shostakovich reportedly told fellow composer Edison Denisov that he had ever loathed anti-Semitism.[10] He is also reported to have told musicologist Solomon Volkov, regarding the Babi Yar massacre and the state of Jews in the Soviet Marriage,

… It would be good if Jews could live peacefully and happily in Russia, where they were born. But nosotros must never forget about the dangers of anti-Semitism and go along reminding others of it, because the infection is still alive and who knows if it will ever disappear.

That's why I was overjoyed when I read Yevtushenko's "Babi Yar"; the verse form astounded me. It astounded thousands of people. Many had heard virtually Babi Yar, but it took Yevtushenko'due south verse form to make them aware of it. They tried to destroy the memory of Babi Yar, first the Germans and then the Ukrainian government. But after Yevtushenko's poem, information technology became articulate that it would never exist forgotten. That is the power of art.

People knew almost Babi Yar before Yevtushenko's verse form, simply they were silent. And when they read the poem, the silence was broken. Art destroys silence.[eleven]

Yevtushenko'southward verse form "Babi Yar" appeared in the Literaturnaya Gazeta in September 1961 and, along with the publication of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in Novy Mir, happened during a surge of anti-Stalinist literature during the premiership of Nikita Khrushchev. Publishers began receiving more than anti-Stalinist novels, short stories and memoirs. This fad soon faded.[12]

Composition [edit]

Yevgeny Yevtushenko c. 1979

The symphony was originally intended every bit a single-movement "vocal-symphonic poem."[xiii] By the end of May, Shostakovich had found three boosted poems past Yevtushenko, which acquired him to expand the work into a multi-movement choral symphony[two] by complementing Babi Yar'southward theme of Jewish suffering with Yevtushenko's verses about other Soviet abuses.[xiv] Yevtushenko wrote the text for the 4th move, "Fears," at the composer's request.[2] The composer completed these four additional movements inside 6 weeks,[thirteen] putting the final touches on the symphony on July 20, 1962, during a hospital stay. Discharged that day, he took the dark train to Kyiv to evidence the score to bass Boris Gmiyirya, an creative person he especially admired and wanted to sing the solo part in the work. From at that place he went to St. petersburg to requite the score to conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky.[fifteen]

Yevtushenko remembered, on hearing the composer play and sing the consummate symphony for him,

… I was stunned, and get-go and foremost by his choice of such apparently disparate poems. Information technology had never occurred to me that they could be united similar that. In my book [The Wave of a Manus] I didn't put them next to each other. But here the jolly, youthful, anti-bureaucratic "career" and the poem "Sense of humor," full of jaunty lines, were linked with the melancholy and graphic poem almost tired Russian women queueing in a shop. Then came "Fears Are Dying in Russia." Shostakovich interpreted information technology in his own fashion, giving it a depth and insight that the verse form lacked earlier.... In connecting all these poems like that, Shostakovich completely changed me as a poet.[16]

Yevtushenko added, almost the composer'due south setting of Babi Yar that "if I were to able to write music I would have written it exactly the fashion Shostakovich did.... His music made the verse form greater, more meaningful and powerful. In a word, it became a much better poem."[17]

Growing controversy [edit]

Past the time Shostakovich had completed the first move on 27 March 1962, Yevtushenko was already being subjected to a campaign of criticism,[13] as he was at present considered a political liability. Khrushchev's agents engendered a campaign to discredit him, accusing the poet of placing the suffering of the Jewish people above that of the Russians.[xiii] The intelligentsia called him a "boudoir poet" — in other words, a moralist.[18] Shostakovich dedicated the poet in a letter dated 26 October 1965, to his pupil Boris Tishchenko:

As for what "moralising" poesy is, I didn't understand. Why, as you maintain, information technology isn't "among the best." Morality is the twin sister of censor. And because Yevtushenko writes about conscience, God grant him all the very best. Every morning, instead of morning prayers, I reread - well, recite from memory - ii poems from Yevtushenko, "Boots" and "A Career." "Boots" is conscience. "A Career" is morality. One should non be deprived of conscience. To lose conscience is to lose everything.[nineteen]

For the Party, performing critical texts at a public concert with symphonic bankroll had a potentially much greater impact than merely reading the same texts at domicile privately. It should be no surprise, so, that Khrushchev criticized it before the premiere, and threatened to stop its performance,[fourteen] Shostakovich reportedly claimed in Testimony,

Khrushchev didn't give a damn almost the music in this instance, he was angered by Yevtushenko's verse. Just some fighters on the musical front really perked up. There, you see, Shostakovich has proved himself untrustworthy once more. Let'south get him! And a disgusting poisonous substance campaign began. They tried to scare off everyone from Yevtushenko and me.[20]

By mid-Baronial 1962, singer Boris Gmyrya had withdrawn from the premiere under pressure level from the local Party Committee; writing the composer, he claimed that, in view of the dubious text, he declined to perform the work.[fifteen] Conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky before long followed suit, though he excused himself for other than political reasons.[15] Shostakovich then asked Kirill Kondrashin to deport the work. Two singers were engaged, Victor Nechipailo to sing the premiere, and Vitaly Gromadsky in instance a substitute were needed. Nechipailo was forced to drop out at the terminal infinitesimal (to embrace at the Bolshoi Theatre for a vocalizer who had been ordered to "go sick" in a functioning of Verdi'southward Don Carlo, according to Vishnevskaya'southward autobiography "Galina: A Russian Story", page 278). Kondrashin was as well asked to withdraw but refused.[21] He was then put under pressure to drop the offset movement.[14] [21]

Premiere [edit]

Official interference connected throughout the twenty-four hour period of the concert. Cameras originally slated to televise the slice were noisily dismantled. The entire choir threatened to walk out; a drastic speech by Yevtushenko was all that kept them from doing so. The premiere finally went alee on December 18, 1962 with the authorities box empty but the theatre otherwise packed. The symphony played to a tremendous ovation.[22] Kondrashin remembered, "At the finish of the first movement the audition started to applaud and shout hysterically. The temper was tense plenty as it was, and I waved at them to at-home down. We started playing the second motion at one time, so as non to put Shostakovich into an awkward position."[23] Sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, who was present, said, "It was major! There was a sense of something incredible happening. The interesting part was that when the symphony ended, there was no applause at commencement, just an unusually long suspension—so long that I even idea that it might be some sort of conspiracy. But then the audience flare-up into wild applause with shouts of 'Bravo!'"[24]

Changed lines [edit]

Kondrashin gave two performances of the Thirteenth Symphony; a third was scheduled for fifteen January 1963. However, at the beginning of 1963 Yevtushenko reportedly published a second, now politically correct version of Babi Yar twice the length of the original.[25] The length of the new version tin can be explained not only by changes in content simply likewise past a noticeable deviation in writing manner. It might be possible that Yevtushenko intentionally changed his style of narrative to brand information technology clear that the modified version of the text is not something he initially intended. While Shostakovich biographer Laurel Fay maintains that such a book has yet to surface, the fact remains that Yevtushenko wrote new lines for the viii nigh offensive ones questioned past the regime.[26]

The remainder of the poem is as strongly aimed at the Soviet political authorities equally those lines that were changed then the reasons for these changes were more precise. Non wanting to set the new version to music, yet knowing the original version faced petty chance of performance, the composer agreed to the performance of the new version yet did non add those lines to the manuscript of the symphony.[27]

|

|

|

Even with these changed lines, the symphony enjoyed relatively few performances — 2 with the revised text in Moscow in Feb 1963, one performance in Minsk (with the original text) soon later on, likewise equally Gorky, Saint petersburg and Novosibirsk.[28] After these performances, the work was finer banned in the Soviet bloc, the work's premiere in East Berlin occurring merely because the local censor had forgotten to clear the performance with Moscow beforehand.[29] Meanwhile, a copy of the score with the original text was smuggled to the W, where it was premiered and recorded in January 1970 by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy.

2d to the "Babi Yar" movement, "Fears" was the about viciously attacked of the movements by the bureaucrats. To keep the symphony in performance, seven lines of the poem were altered, replacing references to imprisonment without trial, to neglect of the poor and to the fearfulness experienced by artists.[half-dozen]

Choral symphony or symphonic cantata? [edit]

Scored for bass soloist, male person chorus, and orchestra, the symphony could be argued to be a symphonic cantata[thirty] or orchestral song cycle[31] rather than a choral symphony. The music, while having a life and logic of its own, remains closely welded to the texts. The chorus, used consistently in unison, oftentimes creates the impression of a choral recitation, while the solo baritone's passages create a similar impression of "oral communication-song." Even so, Shostakovich provides a solid symphonic framework for the piece of work - a strongly dramatic opening movement, a scherzo, two slow movements and a finale; fully justifying information technology as a symphony.[xxx]

Influence of Mussorgsky [edit]

Shostakovich's orchestration of Small-scale Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov, Khovanshchina and Songs and Dances of Expiry had an important bearing on the Thirteenth Symphony, as well as on Shostakovich'due south late work.[31] Shostakovich wrote the greater function of his song music later his immersion in Mussorgsky's work,[31] and his method of writing for the voice in pocket-sized intervals, with much tonal repetition and attention to natural declamation, tin can be said to have been taken directly from Mussorgsky.[32] Shostakovich is reported to have affirmed the older composer's influence, stating that "[westward]orking with Mussorgsky clarifies something important for me in my own piece of work... Something from Khovanshchina was transferred to the Thirteenth Symphony."[33]

Recordings [edit]

- Vitali Gromadsky, bass; Men of the Republican State and Gnessin Establish Choirs and Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Kirill Kondrashin, recorded live during 2nd functioning on December 20, 1962 (with original text), released 1993 by Russian Disc. Reissued 2014 by Praga Digital.

- Vitaly Gromadsky, bass; Moscow Philharmonic and Male Chorus; Kiril Kondrashin; recording of Sep 1965 (revised text version); Everest Records LP released November 1967; remastered to CD by Essential Classics 2011 Historic Recording reached 9 in Billboard Usa Classical Chart. The liner notes of the LP land that the tapes were "smuggled" out of the Soviet Wedlock.

- Artur Eisen, bass; Men of the Republican Country Choir conducted by Alexander Yurlov and Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Kirill Kondrashin on Melodiya, recorded in 1965 or 1971 (revised text version) and released 1972.

- Tom Krause (bass-baritone), Philadelphia Mendelssohn Club Male Chorus, Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy. RCA SB6830, recorded January 1970.

- Dimiter Petkov, bass; London Symphony Chorus, London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andre Previn. EMI Classics, recorded in 1980.

- Marius Rintzler, bass; Men of the Choir of the Regal Concertgebouw Orchestra and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Bernard Haitink on Decca Records, recorded 1984 (bachelor on Spotify)

- Nikita Storojev, bass; Men of the CBSO Chorus, City of Birmingham Choir, University of Warwick Chorus, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra conducted past Okko Kamu. Chandos 8540 (LP ABRD 1248), recorded January 1987.

- Nicola Ghiuselev, bass; Men of the Choral Arts Society of Washington and National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Mstislav Rostropovich on Teldec, recorded 1988

- Peter Mikuláš (bass), Slovak Philharmonic Chorus, Czecho-Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Ladislav Slovák. Naxos: viii.550630, recorded 1990[34]

- Sergei Leiferkus, baritone; Yevgeny Yevtushenko, reciter; Men of the New York Choral Arts and New York Combo conducted by Kurt Masur on Teldec (alive performance from 1993)

- Eliahu Inbal, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Robert Holl. Denon (available on Spotify), recorded 1993

- Anatoly Kortscherga, bass, Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, Neeme Jarvi, conductor, Deutsche Grammophone, recorded 1995

- John Shirley-Quirk, bass, Düsseldorfer Symphoniker, David Shallon, conductor, Musica MundI, recorded 1995

- Sergei Aleksashkin, bass, Chicago Symphony Chorus, Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted Sir Georg Solti. Decca, recorded in 1995

- Sergei Aleksashkin, bass, Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra, Rudolf Barshai, Vivid Classics, recorded 2000

- Sergei Aleksashkin, bass; Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks and Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks conducted by Mariss Jansons on EMI Classics, recorded in 2005 (available on Spotify)

- Jan-Hendrik Rootering, bass; Netherlands Radio Choir and Combo Orchestra conducted by Marker Wigglesworth, BIS Records (2006)

- Alexander Vinogradov (bass), Huddersfield Choral Order, Purple Liverpool Philharmonic Choir, Regal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra conducted past Vasily Petrenko. Naxos: 8.573218, recorded 2013

- Alexey Tikhomirov, bass; Men of the Chicago Symphony Chorus, Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted past Riccardo Muti. CSO Resound, recorded in 2018 (live performance) (available on Spotify)

- Michael Sanderling, Dresdner Philharmonic, 2019 (available on Spotify)

- Sergei Koptchak, bass;[35] Nikikai Chorus Group and NHK Symphony Orchestra conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy on Decca Records (live performance)

- Anatoli Safiulin, bass; Male Chorus of the Yurlov State Academic Russian Chorus and USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra - State Symphony Capella of Russia conducted by Gennady Rozhdestvensky.

See too [edit]

- In Memoriam to the Martyrs of Babi Yar

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ a b c d MacDonald, 231.

- ^ a b c d e f Maes, 366.

- ^ a b c d e Wilson, 401.

- ^ Blokker, 138.

- ^ a b c Wilson, 402.

- ^ a b c Blokker, 140.

- ^ a b As quoted in Wilson, 401.

- ^ Wilson, 268.

- ^ A Vergelis, Terror and Misfortune, Moscow, 1988, p. 274. Equally quoted in Wilson, 268.

- ^ Wilson, 272.

- ^ Volkov, Testimony, 158—159.

- ^ Wilson, 399—400.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, 400.

- ^ a b c Maes, 367.

- ^ a b c Wilson, 403.

- ^ Quoted in Wilson, 413—414.

- ^ Quoted in Wilson, 413.

- ^ Maes, 366-seven.

- ^ Quoted in Fay, 229.

- ^ Volkov, Testimony, 152.

- ^ a b Wilson, 409.

- ^ MacDonald, 230.

- ^ Quoted in Wilson, 409—410.

- ^ As quoted in Volkov, Shostakovich and Stalin, 274.

- ^ Wilson, 410.

- ^ Fay, 236.

- ^ Maes, 368.

- ^ Wilson, 410 footnote 27.

- ^ Wilson, 477.

- ^ a b Schwarz, New Grove, 17:270.

- ^ a b c Maes, 369.

- ^ Maes, 370.

- ^ Volkov, Testimony, 240.

- ^ "SHOSTAKOVICH: Symphony No. 13, 'Babi Yar' - eight.550630". 2019-01-16.

- ^ "Decca Music Group | Catalogue".

References [edit]

- Blokker, Roy, with Robert Dearling, The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich: The Symphonies (London: The Tantivy Printing, 1979). ISBN 978-0-8386-1948-3.

- Fay, Laurel, Shostakovich: A Life (Oxford: 2000). ISBN 978-0-xix-513438-four.

- Figes, Orlando, Natasha'southward Trip the light fantastic: A Cultural History of Russian federation (New York: Picador, 2002). ISBN 978-0-312-42195-3.

- Layton, Robert, ed. Robert Simpson, The Symphony: Volume 2, Mahler to the Present Day (New York: Drake Publishing Inc., 1972). ISBN 978-0-87749-245-0.

- MacDonald, Ian, The New Shostakovich (Boston: 1990). ISBN 0-19-284026-6 (reprinted & updated in 2006).

- Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Printing, 2002). ISBN 978-0-520-21815-iv.

- Schwarz, Boris, ed. Stanley Sadie, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London: Macmillan, 1980), 20 vols. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

- ed. Volkov, Solomon, trans. Antonina W. Bouis, Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich (New York: Harper & Row, 1979). ISBN 978-0-06-014476-0.

- Volkov, Solomon, tr. Antonina Westward. Bouis, Shostakovich and Stalin: The Extraordinary Relationship Between the Corking Composer and the Brutal Dictator (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004). ISBN 978-0-375-41082-six.

- Wilson, Elizabeth, Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, 2d Edition (Princeton, New Bailiwick of jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994, 2006). ISBN 978-0-691-12886-3.

External links [edit]

- Texts of the poems in Russian and English translation (oroginal text).

What Is A File With No Background Called,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symphony_No._13_(Shostakovich)

Posted by: daviskniout.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is A File With No Background Called"

Post a Comment